The Jerry Kugel Story

Building Rods And Breaking Records

By Gray Baskerville

Photography: The Rod & Custom Archives

Early Sunday morning on June 5, 1972, I met Jerry Kugel, a pal of Bud Bryan, Rod & Custom’s editor. We were in China Town (in Los Angeles) to participate in the great Duel of the Deuces. During our day-long drive-a-thon, Koogie and yours truly discovered we had two things in common: an undying love of the salt and our daily drivers (a pair of full-fendered ’32 Ford roadsters).

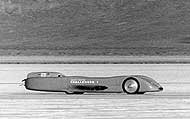

Although my first salt experience was in 1956 and his was in 1959, we associate one person with inspiring our devotion to the salt—Mickey Thompson. In 1958, my dad sent me back to the salt to cover an event for Motorcyclist magazine, a title that had been in the family since 1919. I don’t remember much about the bikes; I only remember the vision of Thompson cutting away a portion of his ’liner’s cowl. The wind caused the aluminum skin to collapse around his hands during his quest to become the first guy to run 300 at Speed Week. The next year, Jerry received a similar career-altering jolt. He had driven up to Bonneville to watch Thompson’s new Challenger after following its construction in Hot Rod magazine—“My buddies and I drove down to the three-mile so we could get a good view of Thompson’s first full pass,” he says. “When he flashed by and shifted into High, the sight and sound that car made hooked me on the salt for life.”

However, Jerry’s life actually began 20 years before in Chicago, Illinois. His folks, Joe and Violet Kugel, left the Windy City in 1946 and settled in Montebello, California, a sleepy suburb of Los Angeles. As Jerry says, “Dad opened a paint store in East Los Angeles and Mom stayed home to raise me, my brother, and my sister. I was in the eighth grade and on my way home from Catholic school when I saw my first rod—a chopped ’34 five- window with a wicked candy apple paint job. I was so dazzled that I almost ran my bike into the parked car.”

During his junior year in high school, the clan Kugel moved to nearby Whittier, which had been a hot-rodding hot bed since the ’30s. The change of venue was a plus for the 16-year-old Jerry; “There were no shop classes at my old school, but Whittier High had them all, including auto shop. Not only did auto shop look like fun, but I had just bought a Model A and wanted to learn how to work on it.” Shortly after Jerry sold his A and bought a ’39 Tudor, the fit hit the shan, or in Jerry’s case, hit papa Joe; “I got pulled over for street racing. The cop kept writing until he filled both sides with equipment violations. Dad drove me to court and the judge took my driver’s license for 30 days and told me to fix my ’39 and bring it back to be signed off. My dad had other ideas. ‘No need to fix it,’ he said, ‘because we’re going to sell it.’”

But being rodless had its advantages. Jerry’s daily bus ride to school took him down Whittier Boulevard and right by Ak Miller’s Garage. Miller—Whittier’s legendary hot rodder, street racer, race car builder, and story spinner—worked on some of the hottest iron in the surrounding area. After a while, Jerry would get off just before Ak’s shop for a closer look at the action. “When I got enough nerve up to ask Ak for a job,” Jerry says, “he told me to go away. After I graduated from Whittier High, I went to work for Mark C. Bloome [a Southland tire store chain—GB], entered Fullerton Junior College, joined the Army reserve (the draft was still in place), and bought a ’40 DeLuxe coupe. The ’40 cost me $800 but it was nice, with a small-block and good black paint, and Jerry Eisert [a fabricator for whom Jerry Kugel had just started working—GB] helped me make some additional modifications.”

However, Jerry’s career with Eisert came to a screeching halt in 1960 when Uncle Sam selected him for a six-month stint in the Army. Jerry recalls, “After I was discharged, I went by Ak’s again; this time, he gave me a job sweeping the floor.” Miller, duly impressed by the various skills that Jerry had acquired from Eisert as well as from the auto shops that he had attended in high school and junior college, quickly promoted him to commission work. Soon, Jerry was doing tune-ups, lube jobs, rebuilds, and performance stuff on any car that came through Miller’s front door.

Meanwhile, Jerry began “legally” racing his ’40, first at the lakes and then at the drags. However, the sight and sound of Thompson making that last shift at the three-mile still haunted him. I’m going to do that, he thought, and in 1962 he did. A guy by the name of Red Holmes had become pals with Jerry, and they decided to go land speed racing together. “We found a chopped ’34 for sale in the classified section of the Los Angeles Times,” says Jerry. “It had no engine and no front sheetmetal, but it did have a bitchin’ body and its 4-inch chop was superb. We got a 265ci small-block Chevy and I opened it up to 274 inches, and added a set of aluminum pistons, a cam, and Hilborn injectors. Our first run at El Mirage was around 150 mph, and we upped that to 163 at Bonneville running in the D/Competition class.”

One of the many benefits of working for Ak Miller was his relationship with Ford. Miller was able to talk Ford into giving him one of their 260-inch V-8s, which he, in turn, gave to Jerry. Jerry was enchanted. He had an engine that few had bothered to modify. In fact, he got one of the first five port-injectors that Hilborn ever made for the small-block Ford; the other four went to Dan Gurney. Jerry replaced the Chevy with his new injected Ford and went on to break the E/Competition Coupe record in 1963 with a 168-mph pass. But Jerry and Red were getting tired of the coupe. As Jerry says, “It was dark, too confining, and not competitive with the far more aerodynamic Studebakers. In 1964, Red and I sold the ’34, kept the engine, and bought a ’32 coupester—a five-window with the top cut off. The coupester was far more roomy and Big Daddy [Jerry’s name for Holmes—GB], who couldn’t fit in the ’34, could drive it too.”

However, the topless coupe purchased from Jerry Tucker was also sans engine and transmission; “I initially put in our 260 and went 165 mph, much to Ford’s delight,” Jerry adds. “They showed their appreciation by giving me a 289.” Jerry reciprocated by running over 180 mph and then over 200 mph with a Miller throwaway. “Ak loved to race at Pike’s Peak with a big-block Ford in his sports car.” Well, Miller blew the Ford and gave the remains to Jerry, who patched it up and built his own injectors. Jerry’s injector was indicative of his growing ability to assemble a part out of unrelated pieces.

Jerry’s home-brewed “squirts” consisted of a stock Ford two four-barrel intake manifold that he modified by drilling and tapping each runner as close to the intake valve as he could. Next, he installed a set of Hilborn nozzles. He then borrowed a three-holed throttle body that came from a helicopter engine and adapted to the * top of the manifold’s plenum chamber. The center hole was blocked off so he could use a Hilborn barrel valve, which he fed with a remote-mounted Gilmer belt-driven (Jerry feels he was one of the first to use a tooth-drive arrangement—GB) No. 420 Hilborn fuel pump. Not only was Jerry’s first komponent eye-tractive [he and his injector were on the Nov. ’67 cover of Popular Hot Rrodding—GB], but it worked. Miller arranged to put the engine on Autolite’s dyno, and a carbureted baseline of 482 hp was recorded. While Ak and dyno-dude Art Chrisman went to dinner, Jerry and Holmes quickly installed the injector and waited for the boys to return. Jerry recalls that both Chrisman and Miller looked at the injector, winked at one another, and then stood back in amazement when the patched-up 427 immediately fired and idled like a stocker. A couple of pulls, a jet change or two, and presto-Koogo—525 hp at 6,500 rpm. The eclectic-empiricist nature of a hot rodder had won again.

The home-brewed injected 427 powering the Holmes-Kugel entry responded in 1968 with a pair of 200-plus mile-per-hour runs, making their highboy the first unblown gas-burning roadster in history to top 200 at the salt, and putting Jerry in the 200-mph club. Jerry then sold the car and found himself driving Autolite’s Lead Wedge, a battery-powered electric car that set a land speed record of 134 mph. Jerry’s fee was a well-used 427-inch SOHC motor that was prepared by Chrisman for an LSR pickup truck driven by Mario Andretti.

So here was Jerry with a fuel-injected cammer and nothing to put it in. The answer was simple: Build a modified. The modified was essentially a fiberglass replica ’27 T placed on a Peek Brothers–built chassis and powered by the injected 427ci “sock” motor that Ford gave him. It also became a Rod & Custom multi-segment project car in 1969. The project went swimmingly until its shakedown tests at the salt flats. When Jerry reached speeds over 240 mph, the modified wanted to drive itself off the course. Jerry fought the problem, even allowing other veteran salt-flat drivers to take a ride, but they too lost control. It wasn’t until a chance look at the car while it sat on blocks at Jerry’s garage that he noticed the body wasn’t square to the world. By then Jerry had sold the cammer to Jim Lattin and the rest to Gordon Hoyt, one of his coworkers at Miller’s Garage.

The reason the modified became chopping-block material was that Jerry’s nine-year career at Miller’s had come to an end. The “kid,” as Miller called him, decided to go out on his own, and opened a general repair shop in Whittier doing tune-ups, brake jobs, and overhauls. Although business was good, his association with Bryan soon led to a career-altering roadster project. “I wanted a fill-in between jobs so I began asking around about the availability of a Deuce,” he says. “One of the LA Roadsters guys—I think it was Neil East—knew of a basket case for sale. First, he cleared it with his fellow club members before he gave me the name of its owner.” The ’32 was one of those “take-aparts” that never got * reassembled, and Jerry bought it for $1,000—a princely sum 33 years ago. To better illustrate how small the world really is, the guy from whom Jerry bought the car came up to him at last year’s Hot Rod Reunion, reintroduced himself, and then said, “I sold that car too cheap.”

Jerry’s gennie had all the cherry sheetmetal and brightwork, but his newly acquired Deuce’s buggy-sprung suspension—like that of his old ’40—didn’t wow him. So the ever-eclectic Jerry borrowed a leaf from Joe Cardoza’s suspension book and adapted a set of XKE Jaguar front and rear suspenders to his roadster’s framerails. It took him a year, but by 1972, Jerry was pussy-footing around Whittier in what would become a test bed for his new komponents. Although it was lost on management, we at R&C could see that street rodding was becoming increasingly popular. So, against a backdrop of gas lines, rising insurance rates, and tightening emissions standards, we created Chevy Up—a 283 that was the brainchild of one of our lunchtime rap sessions. It was an attempt to build a low-cost, low-emission, flat-torque engine by combining both OEM and aftermarket parts. But we needed a wrench—and flat-rating Jerry knew how to twist them Snap-ons.

The motomorphasis of Chevy Up started as an untrained junkyard dog that dirtied Edelbrock’s pristine dyno. As time went on, the mongrel became a purebred and ultimately found a home under the hood of another roadster, my old thirty-shoe. But its finest hour was at El Mirage in 1975, making beer runs in Jerry’s latest race car. As Jerry says, “My modified wasn’t a traditional hot rod; it didn’t have that nostalgic look.” This project featured a experience had come to the rescue and the beer tasted even better than last month’s.

But Jerry felt times were changing. “Frankly, I made my money doing tune-ups, brake jobs, and general repairs—the street rod thing was strictly a sideline, something to occupy my brain between turning rotors or charging a battery. I liked to make the engines run well, but to do so began to violate the smog laws, and I really couldn’t afford all the new diagnostic devices that were coming on the market.” So Jerry reluctantly phased himself out of the general-repair garage business and moved into the now-popular street rod movement.

It was during 1976 that Jerry began a multi-part series with HRM titled “How To Build a Street Rod,” featuring a 50/50 mix of OEM and aftermarket reproduction parts, followed by a similar project employing all reproduction parts. From these and other projects, Jerry started to offer an ever-widening line of komponents that ran the gamut from shortened Ford water pumps and frame-horn repair kits to complete adapter kits that mated XKE Jaguar front and rear suspensions to early Ford frames.

Meanwhile, Jerry also solved another problem affecting his new highboy. He was having difficulties ducting fresh * air to the injected Chevy that powered the little roadster. Jerry’s answer was simple; “I’ll just make my own air.” So, like his former boss Ak Miller and Miller’s employees Big “Bull” Edwards and Jack Lufkin, Jerry made the switch to a pair of hairdryers blowing into a set of Hilborn injectors, and the rest is history. The first time out, Jerry ran 221 on a 200-mph record. Over the ensuing years—until he retired the car in 1995—his roadster would reach the 250-mph mark, getting both of his sons, Joe and Jeff, into the 200-mph club, and it did so without ever spinning out or becoming uncontrollable. The roadster’s place was eventually taken by Lionel Pitts and Dave McDonald’s ’92 Pontiac Trans Am, which the Kugels bought and upgraded in 1997. The Pontiac ultimately became the first American-built passenger car to exceed 300 mph.

In 1985, 14 years after he went into the general-repair business for himself, Jerry said adios to working on stockers. He opened a new shop in La Habra, California, brought his wife Judy and their kids into the business, and began a full-time involvement with the cars that had been only a sideline just nine years before. As street rodding evolved from T-buckets and resto rods to trad rads and handbuilt smoothies riding on aftermarket suspension systems, the “kid” followed suit by designing and assembling many of the cars and components that have become street rodding trend setters.

Like M/T’s shift into High, Jerry hasn’t forgotten an old dream he and I shared: to drive a car to the flats on pump gas, run 200, and then drive home. Today, he’s building Deuce-like specials that he calls “Murocs.” The last Muroc may be slated for a turbo transplant and a round-tripper to Bonneville with a 250-mph boogie in between. Then there’s old 265. It’s neither gone nor forgotten—just on display at the NHRA Motosports Museum. Plus there is a new and vastly improved turbocharged Chevy on hand. Jerry, Joe, and Jeff Kugel were the first to run three bills in their door-slammer. Jerry Kugel loves new projects, and three bills in the family hairblower has got the “kid” thinking all over again.

|

|

|

|

After Jerry graduated from Whittier High and went to work for Jerry Eisert, he was able to afford this ’40, complete with its small-block Chevrolet, and race it at such varied SoCal venues as El Mirage, Riverside (half-mile drags), and Pomona.

|

Mickey Thompson’s shift into High at the three-mile began Jerry’s love affair with land speed racing that ultimately led to fielding the first Detroit-built passenger car to exceed 300 mph.

|

In 1962, Jerry returned to the salt with his new partner Red Holmes (wearing the white pith helmet) and their chopped ’34 coupe. Hoodscoops were made from parted Corvette rocker covers.

|

In 1963, Miller’s close relationship with Ford Motor Co led to an engine swap—a 260 Ford V-8 for the existing 274 small-block Chevy. Jerry responded with a new record in the E/Comp Coupe class with a 165-mph average.

|

Jerry returned to the salt in 1965 with his coupester, a ’32 five-window with its top removed.

|

In the meantime, Ford, tickled to death with the performance of his 260, gave him a 289 that ran a best of 178 mph in 1967.

|

However, Jerry’s big gun, an alky-burning, home-brewed injected 427, had enough FoMo-go to run 205 and get Jerry into the 200-mph club.

|

In 1968, Jerry was still working for Miller but had gotten rid of the coupester and was looking for a new ride. When Ford wouldn’t let Autolite’s Danny Eames drive its Lead Wedge, Miller asked Jerry if he would take Eames’ place. Jerry averaged 138 with a best of 141 and got a Chrisman-built, Hilborn-injected 427 SOHC V-8 for his trouble.

|

The Peek Brothers—salt racers and chassis builders from Littleton, Colorado—offered to donate a modified roadster chassis to the cause. Former R&C editor Bud Bryan took this photo of the partially finished modified in Jerry’s garage (photo dated March 1969). The Kugel & Holmes’ B/Modified Roadster ran a best of 240 on 50 percent and would have gone faster if it weren’t for subsequent modifications to the front and rear suspension and a slightly cocked body that caused the car to spin when it reached over 240 mph.

|

Two years later (in June 1972), the Koogster and your ol’ Dad were having at it on the Pasadena freeway doing the Duel of the Deuces chingo. Best of all, we still have our rods—although mine is currently in a thousand pieces and being restored by Chrisman Cars.

|

Chevy Up—aka “the smog motor”—was R&C’s low-buck answer to the realities of the early ’70s—namely, emissions and mileage. We settled on a worn-out ’64 283 with double-hump heads. It was baselined (as is), completely rebuilt, retested, then fitted with aftermarket parts from Holley, Edelbrock, MSD, and Isky. The smogger was given one last pull and parked. Two months later (July 1975) it became the beer runner with a best of 154 mph at El Mirage, thanks to the tuning efforts of Darryl Buehl (left) and the Koogster.

|

Running concurrently with the Bonneville/smogger project was Jerry’s first magazine-series car titled “How to Build a Hot Rod.” This photo of Terry Riley (left) and the “kid” taken in March 1975 shows the completed chassis featuring Jerry’s front and rear XKE swap kits and shorty water pump.

|

|

Jerry Kugel

Jerry Kugel

Jerry Kugel

Jerry Kugel