Wild In The Streets

The Adventures Of Dick Kraft

By Dick Martin

Photography: Dick Kraft

What better place to meet Krafty Dick Kraft than at John Force’s incredible drag racing headquarters in Yorba Linda, California? Recently, I was fortunate enough to tour John Force’s high-tech facility as part of a small group that included, among others, Ed Iskenderian and Dick Kraft. When John arrived to show us around, he spotted Dick and Isky; the roles were reversed and John became the fan for a change. It makes sense that he should feel this way—when John Force was in diapers, Dick Kraft was ringing out his new state-of-the-art rail job at the Santa Ana Dragstrip.

Catching The Racing Bug

Dick was born in the sleepy California farming community of Anaheim in 1921, where the smell of citrus groves—not exhaust fumes—permeated the air. “Some dang fool gave me a roadster when I was 14 and ruined my whole cotton-pickin’ life,” begins Dick Kraft on his entry into the world of hot rods. “Then, I had a ’29 Model A with Kelseys and a Winfield head that I paid for by working on the family ranches. I wasn’t getting anywhere [with the four-banger] so I bought a ’32 roadster with side mounts and 18-inch wheels for $200. In high school, we had a car club called the Plutocrats. Every Saturday night, we would street race to hold [onto] our number-one status. All the guys in the club would later go on to hold records. I ran the ’32 only one time at the lakes and turned 98 mph.”

Street racing, while we don’t condone it, is a part of hot rod history. The legends of the sport didn’t become heros by collecting stamps as kids—they were racers. Dick recalls: “Before you were 18 [in Orange County], if you got tickets, you had to go to traffic school on Saturday in Santa Ana. I went to traffic school from the time I was 16 ’til I was 18 without a Saturday morning off.”

Toning Up

Rod & Custom ran a photo in the Jan. ’02 issue showing Dick at speed in The Bug. Some readers may have noticed the size of Dick’s arms. Dick could bench-press 300-plus pounds in those days, and what better place to hang out with a body like that than at the beach? Naturally, he went for the girls, but the real draw to places like Newport Road (between neighboring Santa Ana and Costa Mesa) was street racing.

“I really went to the beach to street race,” says Dick. “When there wasn’t anyone to race, we’d get kind of bored and go out into the parking lot and street fight.” The beach and sailors went together, and after a few brews, the boys in white sometimes had a differing of opinions with guys like Dick. You can probably guess who got the upper hand.

Dick credits his high school shop teacher with encouraging him to attend night school to learn a trade and calm down. Young Dick learned to work with machine tools and equipment, building manifolds and headers, later going on to Fullerton Junior College.

In The Marines

When the war broke out, Dick decided to join the Merchant Marines. Dick was rather enterprising when it came to picking up an extra buck while serving his country. “I had never smoked a cigarette in my life, but they allotted me three cartons a week and I had a locker full. I’d sell them or trade for guns.” He was thinking ahead to when the war would end and the money he made by selling to guys with a nicotine habit would fund his racing habit. Meanwhile, Dick’s friend and future Indy great Jack McGrath was building Dick a hot engine. “When I got home,” Dick says, “I wanted to go racing; I didn’t want to be putting an engine together.”

Dick had two things on his mind during the war: staying alive and racing. Once, with a few hours off from his ship, Dick wasted no time getting to Anaheim where Jack McGrath was waiting for him with his ’32 and a rope to tow the bare-bones roadster to a midnight street race.

“There was no starter, no teeth on the flywheel, no generator, and it had one motorcycle light,” recalls Dick. “It was a pushmobile—we had to give it a shove to start it. We towed it on a rope all the way to the Piccadilly Drive-In in West L.A. I beat every guy there that night. I beat Jack and Manuel Ayulo—they both had ’32 Ford roadsters and my car was much lighter. My one light was getting dim so we towed it home and put it away. That was on Saturday night. On Sunday morning, here come 4,000 marines on Pier 91. We loaded them and headed for Pearl Harbor.”

Dick decided to stay in the Merchant Marines after the war ended, but the urge to feel the dust of the dry lakes in his face was stronger than the spray of salt water. It was heaven to set foot, briefly, on the lakes in 1946 when he ran his prewar T at Harper. He recalled how, with a few days leave, he, McGrath, and some friends built what looked like a cross between a kayak and a Soap Box Derby racer.

“I bailed off the ship on Friday and went home. I had the engine that McGrath built and I wanted to get going on a car—I only had two or three days before I had to be back on the ship. I built the frame out of 2x2 box tubing. All I had was a gas welder, so we welded the tubing together with that. We didn’t have any springs, so we welded the front end and the rear end [with the gas welder] to the axles. We sent somebody to steal a Coca-Cola sign to make the body out of. We didn’t have any rivets, so we screwed the halves together with stove bolts. By Saturday, we finished the thing and I took it to El Mirage on Sunday and ran 135 mph. After seeing the guys at the lakes and having my new motor, I decided I’d had enough [of Marine life] and signed off that bucket of bolts for good.” Dick stayed in the Merchant Marines until 1947. When he left, he wasted no time becoming a challenger.

Drag It Out

Dick was an avid street racer, but as soon as C.J. “Pappy” Hart and Creighton Hunter started holding legal drag races at a seldom-used taxi strip, Dick became a regular competitor. For the first time, guys like Dick could race legally on a paved track with cops watching the action rather than chasing it. With this fledging sport came a different kind of race car. Running for top speed at the lakes was one thing—you had miles to do it. But drag racing consisted of just a quarter-mile. Top speed mattered, but acceleration mattered more. As a result, vehicle weight became a big factor.

Dick showed up at Santa Ana in 1950 with a contraption that consisted of four wheels, a motor, and a seat. The only piece of sheetmetal on the car was the cowl. Dick gave his rail job a name: The Bug. His single-seater was registered as a roadster, though we now know that it became the world’s first dragster. Before its drag racing debut, The Bug had to earn its keep on Dick’s parents’ orange grove—as a weed-sprayer. Dick commandeered what was left of the ’27 T frame and made a race car out of it. The weed-sprayer ran a number of times at Santa Ana with both a roadster body and a coupe body before it was stripped to the bone.

Running at the drags became part of Dick’s routine, sharing time with his other hobby: surfing. It was not uncommon for him to appear on the start line at Santa Ana with his typical racing gear: goggles and damp swim trunks. “We’d body surf at Newport, jump in the thing, and go drag racing. Running nitro with my swim trunks on and burning the hair off my chest—boy, those were the days,” laughs Dick.

Back To Work

Dick worked for his brother on his orange grove maintaining the farm’s equipment. At the same time, he worked for George Barris to pay off the debt incurred for the Kraft Special’s chrome. “My specialty was chassis work and engines. I never built a car that spun out on me,” he says.

Krafty had a knack for spinning out the competition, though, as well as getting the most out of his hot rods. He appeared to have an unlimited amount of cars, when in reality he was switching the bodies. There was another reason competitors called him Krafty, and it was the paradox that is Dick Kraft: mixing the crude with the graceful. Just when fellow racers thought they had him figured out, Dick pulled a 180. It’s hard to believe that the same man who built The Bug also constructed two of the most beautiful track roadsters to appear at a race course or car show. His blue car graced the Oakland Roadster Show in 1950 after being exposed to the all-encroaching dust and dirt of El Mirage, running 122 mph. The Kraft Special (the red car) was displayed at the ’51 Oakland show. Dick’s Kraft Special was lettered professionally, dripping with that expensive shiny chrome and constructed like a Swiss watch.

Hot Rod Or Sports Car?

The sports-car races started to attract hot rodders, and Dick’s friend and part-time employer George Barris was one of them. Barris’ shop was drawing an increasing share of the sports-car set, and he became interested in what was going on 100 miles east of his business. Palm Springs in the early ’50s was a quiet little desert community that had a sparsely used airport. It was easy to shut the runways down and hold amateur sports-car races on the weekends. Barris threw out a challenge to Dick: “Let’s get you out of that T shirt and Levis and into a white shirt and tie, and join the Sports Car Club of America.” The “wire-wheel car” (Rudge wire wheels cut down to 15 inches for more strength), as Dick refered to his hot rod sports car, appeared on the cover of the Oct. ’54 issue of Hot Rod magazine. “I did the frame, the front end, the rear end, the transmission, and the motor, and my friend Art Ingles did the body,” remembers Dick. When Dick mentioned doing the frame, he was referring to a sophisticated truss-tubular chrome-moly chassis that only someone with engineering savvy could design and build. It rivaled anything that came out of Italy and showcased the kind of talent Dick possessed.

Border Bug

Dick Kraft’s life reads like folklore. He’s done it all—his way. He’s still doing it all, too, even down to resurrecting The Bug—twice. Like so many old hot rods, The Bug might have been scattered into oblivion had it not been for an inquiry by Don Garlits. “When Don Garlits got his museum going,” says Dick, “he wrote to me and said, ‘I understand you have parts of The Bug lying around at your brother’s ranch. Would you put it together for me?’” It wasn’t too long before the word got out: Dick Kraft is putting The Bug back together. Then Steve Gibbs, vice president/director of the NHRA Motorsports Museum, asked Dick, “Why don’t you put one together for the museum?” Dick has the original frame and some other parts, so “we put one together for the museum in Pomona.

Each rail job is made up from parts from the original,” he says. During this time, Dick had retired to Mexico for a number of years and still maintains a home there. His wife of 30 years, Margarita, has been by his side helping Dick build a new version of his rail: The Bug II.

While Dick doesn’t have those 16-inch arms anymore, they haven’t given way to buggy whips, either. He still skips rope every day, gets up at the crack of dawn to join his buddies for breakfast, and generally tries to stay in trouble. Once Dick gets The Bug II on the street, it’s inevitable that he’ll get pulled over. Let’s just hope it’s for curiosity this time.

|

|

Dick was one of the original California beach boys, splitting his time between the dry lakes and Newport Beach. A health nut, Dick worked out regularly and could press 300 pounds with those 16-inch arms. He went to the beach to street race and, when things got a little slow, street fight. When most guys were straining to reach 100 mph in 1941, Dick had pushed his T to 121 mph at Muroc.

|

Imagine screaming down the quarter-mile to 116.50 mph in this baby! The front tires are Wards Riverside DeLuxe tractor tires from the family orange grove—maximum speed rating: 35 mph. Dick sometimes arrived at Santa Ana in damp swim trunks from a morning of body surfing before slipping behind the wheel. Safety equipment consisted of a seatbelt and goggles. To keep that fighting spirit, the seat was from a B-17.

|

Dick was still in the Merchant Marines when he posed with his dad in front of their Anaheim home (it’s still standing) in 1946. Looking more like a defector from the Soap Box Derby, Dick, with a couple of days off from his ship, beat it home on a Friday, threw this beauty together by Saturday, zipped up to El Mirage on Sunday, ran 135 mph, and was back on the ship on Monday. The bellypan is from a Coca-Cola sign.

|

Dick’s blue track roadster was the ultimate hot rod in both looks (’50 Oakland Roadster Show participant) and performance (122 mph at El Mirage). His T had the qualities of a Frank Kurtis product. Art Ingles, a master metal-shaping specialist, was employed at Kurtis Kraft, and he handformed the hood and stunning grille for Dick in 1948.

|

This classic battle between Dyno Don Nicholson and Dick Kraft at Santa Ana took place before Dick began stripping his T into a rail job. Dick couldn’t remember who won this match, though it looks like he’s slightly ahead of Dyno Don.

|

While in high school, Dick learned of the dry lakes and wore grooves in the road getting to El Mirage, Harper, and Muroc, racing every weekend. During his first time at the lakes in 1938, Dick ran 98 mph in a ’32 roadster. Dick knew lighter was faster and reverted to running Ts from that point on.

|

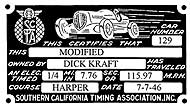

His zeal for the lakes never dampened, and while still in the Merchant Marines, he got off the ship long enough to run this ’27 T roadster on Chevy rails to 115 mph at Harper dry lake in 1946.

|

Dick built his tube-frame roadster for a new form of competition attracting hot rodders in the ’50s: road racing. “I was working for George Barris when [we joined the Sports Car Club of America.] George had a C-Jag that he drove and I raced my car a couple of times at the Palm Springs airport course in 1951.” Close friend Art Ingles formed the beautifully crafted aluminum body.

|

Dick hadn’t seen this photo since the ’40s, then High Desert Roadsters member Jerry Olson of Victorville, California, brought it to our attention. Olson was given an ancient scrapbook that contained other dry lakes stars from the ’40s. We asked Isky, John Athens, Nick Arias, and Dick to identify some of the participants. They only came up with a few names. Recognize anybody? Let us know so we can run more of these vintage snaps.

|

Dick in his Kraft Special (later called the Highland Plating Special) doesn’t look particularly thrilled to be sitting at a car show (those are racing trophies) even if it was the second annual Oakland Roadster Show. “I built cars to drag race, street race, and run at the dry lakes—not to look at. I built cars to drive; I put 60,000 miles on that car and won 20 trophies at Santa Ana,” says Dick. “I bought the ’24 T from a relative who had it on a chicken ranch in Orange for a hundred bucks and drove it home.”

|

Except for the hubcaps, only the bare essentials were tolerable on what was to become the first dragster. The sheet of aluminum over the Strombergs prevented some of the 30 percent nitro from splashing back on Dick’s face. There are two copies of The Bug, one at the NHRA Motorsports Museum in Pomona, California, and the other at Don Garlits’ Museum of Drag Racing in Ocala, Florida.

|

Nothing was normal in the ’70s when it came to the show circuit. Barris built his share of wild things. Dick had worked with George Barris since the early ’50s and helped build the World’s Fastest Snowmobile in 1970. Four Kawasaki engines with 12 beautifully polished expansion chambers pointed in the general direction of the driver.

|

Before The Bug became the first record-setting dragster, it was a humble weed-sprayer on the Kraft family orange grove. That’s Dick behind the wheel at the seventh annual Hot Rod Reunion in Bakersfield, and the guy next to him is former Hot Rod magazine photo editor, Eric Rickman—“my big buddy,” as Dick calls him. School chum Ron Roseberry helped Dick reconstruct the great-great-grandfather to the AA/Fuel dragster.

|

Eighty-one-year-old Krafty Dick is at it again. A half-century later, Dick is building another contraption—The Bug II. That’s a Chevy II four-banger with a couple of 97s residing on a ’24 T frame with a Powerglide, a ’40 Ford rearend, a ’34 Ford front axle, and ’33 Willys steering. Dick promised us he wouldn’t do any street racing in his new rod.

|

|

Wild In The Streets

Wild In The Streets

Wild In The Streets

Wild In The Streets