|

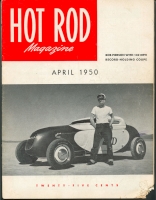

One of the first great tin tops was the Pierson Brothers 1934 coupe built for combat on the dry lake beds in 1949 by Bob and Dick. The brothers started by chopping the top nine inches and leaning the windshield back. Ace engine man Bobby Meeks built a triple-carb 297-inch flathead that pumped more than 300 hp (radical stuff in those days). Bob set a class record at 153 mph and in April 1950 it graced the cover of a promising new magazine called Hot Rod. The coupe continued to be raced by a series of owners, including Dawson Hadley, Jim Evans (1950-51), George Bently, Tom Cobb (1958), Bob Joehnck(1959), Dick Schell, until finally in the early 1980s, when Tom Bryant (1980-1991) bought the car and blistered the salt at 227.33 mph (with Chevy power) along the way setting eight world records. 1949 it was flat black. It was painted the famous Candy Red, White & Candy Blue with 2D in 1950. Now owned by collector Bruce Meyer (1992), it has been lovingly restored back to the way it was in 1949 by Pete Chapouris at So-Cal Speed Shop, with help from Meeks.

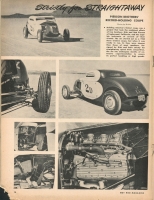

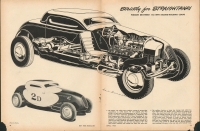

THE WHO'S WHO WITH THE PIERSON BROS COUPE The Pierson Brothers Coupe Fifty-One Years ago, three guys from inglewood took another look at the rules and made hot rod history. April 1950, check out this famous old Hot Rod Magazine cover showing a chopped '34 Ford coupe on El Mirage dry lake. That hammered top is the first thing you see and it's the feature you can't forget. Severely flattened, with armored car slits for windows, it looks as though a building fell on the car. The coupe's driver, a pugnacious-looking rebel in a vintage cork helmet, an unadorned T-shirt, and rolled-up Levis poses proudly. Inside the magazine, a Rex Burnett cutaway reveals the secrets of this 142-mph Russetta Timing Association record-holding racer. Fifty-one years ago, this largely home-built hot rod copped an attitude long before that expression was applied to anything on four wheels. For a brief time, it was the fastest closed car in America. Its wide exposure at the lakes, and in rodding magazines of the period, served to define the postwar American youthful obsession with power and speed. It also helped put Edelbrock Equipment on the high performance map. Stated simply, it's the coupe that beat the roadsters. The Pierson Brothers coupe was a sensation when it topped 140, and soon afterward, it ran over 150 mph. Back then, for many people, hot roadsters defined hot rod. Top of the heap in '49 to '50, the quickest roadsters, with big 296-cid flathead strokers, stripped of everything nonessential, and probably 250 pounds lighter than a hardtop, were hard pressed to top the 130-mph mark. Coupes were declasse. For a long while, the SCTA didn't even consider them to be race cars, an in-your-face gesture to pioneer era rodders like Lou Baney, Lyn Yakel, Bob Rounthwaite, and two brothers from Inglewood, Dick and Bob Pierson, along with their friend (and crack engine builder) Bobby Meeks. All three were members of the Coupes Club of Inglewood and the RTA, of course, because the SCTA wouldn't let them run. "We didn't think coupes were real hot rods," says Alex Xydias, an SCTA Board Member at the time. "We were very conservative guys and these cars didn't fit our pattern. At first, we didn't even believe the numbers. Of course, when Baney and the Piersons started going fast, we had to give in. I actually recruited Bob to run under the (Glendale) Sidewinders banner so we could win the points championship one year."/p> It's hard today to understand what the coupe versus roadster fuss was all about. "Lakes cars were roadsters, modifieds lakesters, and streamliners," Bobby Meeks explained. "But a lot of guys owned coupes and sedans, and they needed a place to run, too. The old Western Timing Association (WTA) would take anything. And then there was Russetta. We were equal to the SCTA in many ways, especially after the SCTA guys saw the light." Coupes were heavier than open roadsters, and until the Piersons and Bobby Meeks began setting records, it was generally thought the closed cars couldn't possibly run as fast as the open roadsters. The last thing many roadster jockeys probably saw was this sleek coupe's deck-mounted Coupes Club plaque as it sped out of sight. A half-century ago, the stalwarts of early hot rod competition were the guys who drove or towed their cars to the dry lakes for a weekend of racing. Faded photos from that era show long lines of scruffy Ford roadsters, their owners patiently waiting for a chance to run the course and storm through the time traps. In the midst of these dust-covered warriors, is an obviously beautifully-built, painted and plated '34 Ford coupe. "You could walk down the line and only find one or two cars that were even painted," Bob Pierson recalls. Why was this particular coupe turned out so well? "Some of the sports car guys had been sneering at our hot rods," Pierson recalls, "so we decided to finish this car like the Midgets and Indy racers, with shiny paint and chromed suspension parts. Dan Gurney, himself a lakes racer, remembers. "When the Piersons showed up with this car, compared to our roadsters, it looked as though it had come from another planet." And there was a meteor behind the wheel. "I was a bombshell, looking for a place to explode," Bob Pierson exclaims today. "Vic Edelbrock [Senior] knew we were using his equipment. We were one of Vic's guinea pigs," he recalls."What we'd learn testing on Sepulveda or Lincoln Boulevards (often topping three figures) on a Thursday night, we'd use at El Mirage on Saturday." Was he worried about hitting someone at those illegal speeds? "There wasn't much traffic in those days," he shrugs. "We'd run till the cops showed up, then scatter." Working at Douglas Aircraft, Bob Pierson learned the rudiments of aerodynamics. He conceived the car's airfoil-like, flat undertail section with its narrow opening that allowed rushing wind to exit across a flat panel and probably helped hold the light rear end down. The stock gas tank was axed and a small racing tank was located alongside the driver, right next to the battery. Pierson's kid brother Dick did much of the preparation, but it was modest Bobby Meeks, an Edelbrock employee for 50 years, who was responsible for the coupe's high-performance flathead--and its unique look as well. "One of my jobs at Edelbrock was to find guys who could be successful racers," says Meeks. "So I recruited them and we helped with the latest equipment." Edelbrock devotees included Bill Likes, Fran Hernandez, Don Waite, Alex Xydias, and of course, the Piersons. "That's why Edelbrock cars had so many records," Meeks says. After the Piersons agreed to prepare their coupe for the Lakes, it was Meeks who decided on the excessive roof chop. "Naturally, we were looking for high speed," he says. "That dictated the narrow shape of the front end, the full belly pan, and the chop..." he chuckles, remembering a history-making night's effort decades earlier. "The rules said the windshield had to be seven inches high, but they didn't specify the angle. So I laid the posts back until you almost lost vision (about 50 degrees), then raised 'em up a bit, and that was it. Those thin plexiglass side and rear windows helped, too." When he first stood back to look at the car, he realized immediately what he had done. "We didn't even paint the racing class letters on at first," Meeks recalls, "because we knew the officials would take one look at it and raise us a class." Besides the severe 9-inch chop, the gutted body was channeled 3 inches. A stock hood was mated to Harry Jones' beautifully crafted race car nose. The frame horns were snipped front and rear and new tubular crossmembers were fabricated. A World War II surplus bucket seat (probably from a tank) and a webbed khaki seat belt comprised the principal safety touches. The top of the steering wheel was cut off, so the driver's already limited vision wasn't further impaired. A flat panel held a row of curved glass Stewart Warner instruments, but it's doubtful they could be read as the stiffly sprung coupe bounced along the dusty course. "After we ran it a few times and realized there was a lot of frame flex," Bob Pierson recalls, "Vic Edelbrock himself boxed the centersection of the framerails, and we added a rollbar for protection and even more stiffness." A '38 Ford tube axle was used with precise '39 Ford cross steering, beautifully fabricated hairpin wishbones, and reworked Ford friction shocks. In the rear was a high-priced piece of technology for the era, made in nearby Culver City. One of Ted Halibrand's alloy quick-change centersections, supported by a modified Model A crossmember and buggy spring, permitted a choice of high-speed gears. The first records were set with a 2.94 rearend ratio. Front tires were ribbed 5.00 x 16 Firestones and 7.00 x 16's were used in back on stock Ford steel rims, still wearing '48 Ford beauty rings and hubcaps. Bobby Meeks was (and still is) a natural mechanic who used much of the same fine speed equipment (Edelbrock high compression heads and triple manifold, Stromberg 48 carburetors with 20 cfm, each more than the popular Stromberg 97's, a Winfield Super H cam, Kong dual point, dual coil distributor and Belond W-2 headers) on this car as many rivals, but his high-level preparation, skilled machining, and careful assembly preceded what later became known as "blueprinting." In his wonderful book, The American Hot Rod, the late Dean Batchelor, himself a successful lakes racer, extolled Meeks' virtues. "Some engine builders became legends in their own time...one of the most prominent, and arguably the best, is Bob Meeks," Batchelor wrote. "What Bobby did to these engines is basically the same thing other builders did, but Meeks gave them his own special touch; partly the result of many years of building engines, and partly from many hours of experimentation on the Edelbrock dynamometer. If any 'speed secret' was in these engines," Batchelor confided, "it was one of extreme care in assembly." This example from Batchelor proves his point. "Bobby developed a jig to hold a slightly tapered core-drill which was run into each of the intake ports a predetermined distance, thus guaranteeing all eight ports were exactly the same size." Meeks would install intake valves so oversized they had to be seated on the flathead block itself; he fabricated a metal divider to separate the Siamese-center exhaust ports on each side. "The 4-inch Mercury crankshaft didn't come along until 1949," Meeks told me, "so we stroked the stock shaft 0.125-inches, bored the block out the same 0.125-inches, and the engine would still rev reliably to about 5,800 rpm." The meticulous Mr. Meeks just did everything a just little better. He experimented with fuels before SCTA authorities realized just how much advantage that practice was. "But we ran that coupe on alcohol in 1949," he insists today. The infamous Edelbrock nitro-methane experiments began a few years later, in the summer of 1951, first with Midget racers at Gilmore Stadium, later with many of the hottest cars in racing. What was the coupe like to drive? "It hunkered down and went where you put it," Bob Pierson recalls. "I used to be considered a hot dog, because I'd pitch the car from side to side, outside the cones, trying to break the tires loose, so the revs would get up even higher. Then when the tires bit, I'd really get on it." Hot rods are known by the name(s) of their original builders, so this '34 will always be called the Pierson Brothers' coupe. But it was destined to pass through several hands over the years. Seldom away from racing, under new management, it continued to run faster and faster. In 1953, then-owner Dawson Hadley achieved 165.23 mph. In 1956, Tom Cobb turned 198.86 mph. In 1991, Tom Bryant actually set more records in the car than anyone else. He achieved the coupe's best speed--227.33 mph, albeit with Chevrolet V-8 power. Present owner and noted historic hot rod collector, Bruce Meyer, of Beverly Hills, California, bought the coupe from Bryant and commissioned Pete Chapouris to restore it to 1950 specifications back when his shop was called PC3G. "I've always loved that car," Meyer explains. "It's the quintessential hot rod coupe. When I bought it, Tom Bryant was still racing it. He wasn't anxious to sell, but thankfully he did. This car just had to be restored to its original configuration. What's remarkable is that it ran well over 200 mph, and the body and running gear were still substantially the way the Piersons and Meeks had built it. Talk about right the first time." Pete Chapouris took what he called an archaeologist's approach to the Pierson coupe's restoration. "It was a raggedy old dog. If it had run one more season, it probably would have fallen apart. Most of the sheetmetal was intact, but over the years, extensive frame bracing had been added," he explains. "I peeled away the layers until it looked exactly like the Rex Burnett cutaway drawing and Tom Medley's photos in Hot Rod Magazine." A perfectionist, Chapouris saved as much of the original steel as he could, and metal master Steve Davis massaged the old panels back into shape. Although they took a few fit liberties and lowered the nose a tad, the restorers left the car's characteristically ragged door gaps. Thankfully, there was enough of the original paint below many accumulated layers so they could duplicate the original candy red and blue hues. "The front A-pillars were shot, so we replaced those," Chapouris explained, "and the rollcage was welded to the body panels, so we had to separate them. But now most of the car is exactly the way it was built." Both Piersons and Bobby Meeks (who also built the car's present engine) helped oversee the restoration. In November 1992, Bruce Meyer held a gala coming-out party for the finished car with a "Who's Who in Hot Rodding?" cast of characters present. Boyd Coddington was philosophical about the return of the Pierson Brothers' coupe. "This is one of our ancestors," he noted. "It's important to understand cars like this one, to know where we've been and where we're going." Since its restoration, the Pierson Brothers coupe has made countless public appearances. It was the first car inducted into the Dry Lakes Hall of Fame. When it's not travelling to shows, it's often on exhibit at the Petersen Automotive Museum in Los Angeles. But Meyer doesn't hesitate to take it out. He raced it up the hill several times at the Goodwood Festival of Speed in England last summer. "It was awesome," he says, "a real challenge, particularly because you can't see out of it. Of all the cars I have, it's the one people find the most interesting. And it's amazing how many people over there knew what it was. Besides saving an important piece of hot rod history," Meyer says, "the fact that so many people can share its significance makes me warm all over." This August, the Pierson Brothers coupe will be one of nine '40s to '50s-era competition coupes--including the car's old nemesis, Alex Xydias' SoCal coupe with its blown Ardun, along with the Chrisman Brothers Model A and the Mooneyham & Sharp '34--on display at the Pebble Beach Concours d'Elegance. So-Cal Speed Shop's Pete Chaporis and his crew are freshening old 2D for a different kind of competition: the lawn at the 18th green. "When we did that car, nine years ago," he said, "hardly anyone had restored a hot rod before. To get the car up to Pebble Beach standards today, with correct cotter pins, castle nuts, instruments, etc.," he says, "we've got a lot of work to do."I've long been a big fan of the Pierson Brothers coupe, so when I was Director of the Petersen Automotive Museum and the opportunity came while setting up an exhibit to drive it on the roof and around the parking structure, I didn't hesitate. The small displacement flathead fires after a few spins and, thanks to its lusty Winfield cam, it "idles" at 1200 rpm. Blip the throttle and the Meeks-prepared flathead responds instantly. There are no frills in the cramped office...just an unlined tank seat, tapered shifter, and cutoff steering wheel. The exhaust notes echo loudly off the walls. Within seconds, we'd set off many car alarms in the parking garage. Inside it's deafening--like driving a motorized snare drum. Nail the gas and the little coupe leaps ahead, obviously eager to run. Peering through the slit of a windshield, I can't imagine the courage it took practicing speed runs in this car late at night on Lincoln Boulevard, let along pointing it towards the far horizon at the lakes or Bonneville and hammering the pedal. The Pierson Brothers '34 remains a key link in the legend of early hot rodding--a raucous fast coupe speeding in harm's way. Dean Batchelor graciously told his readers, "I wish you could have been there, it was great." Surely cars like this were the reason.

|

As raced by Tom Bryant Originally drawn back in the late '40s by the renowned technical illustrator Rex Burnett, this image of the Pierson Brothers coupe has been called Burnett's most famous piece. The Pierson coupe wears era-correct Firestone ribbed tires on '46 Ford-capped 16-inch wheels. Those are the original hairpins--down to the tie rod ends the brothers ran some 50 years ago. Tim Beard and John Carambia shot the car in the proprietary red, white, and blue, while Dennis Rickleffs lettered the car per post-war specs... ...Then, as now, Edelbrock's Bobby Meeks built the 3 5/16 x 3 7/8-inch flathead, but admittedly milder. Even though the 267-inch engine isn't the engine that the brothers ran then, it still sports 1 5/8 and 1 3/4-inch valves and a port and relieve job, but relies on a 404 junior cam and gasoline instead of the original 404 and alcohol combination... ...And there it is: the chop that changed the world. . .the hot rod world, that is. "The rulebook said the windshield had to be 5 inches. They didn't say anything about angle, though," Dick Pierson said. So Dick, Bob, and Meeks just got the desired height by angling the windshield back--a full 50 degrees! The coupe still wears sheets of plastic in lieu of glass. A '39 steering column still pokes up through the floor; the car was converted to cross-steering early on. As for the gauges, they're now Classic Instruments, with a set of original gauges undergoing restoration... ...The black-painted Optima battery has a similar story as the electrics were converted from 6 to 12 volts during the restoration. The car has to be able to start after long periods of sitting, hence the conversion. All wiring wears cloth sleeves as it did the first time around. The original seat was lost, but a B-25 bomber radar seat was sectioned 4 inches in its width to replace the lost seating.... ...That's the Culver City Halibrand quick-change the Piersons ran back in the day. "The car's probably closer to being original than most of the cars out there at concourse," Chapouris said, adding, "everything I could use, I used...it's all original." Bob Pierson standing alongside the coupe behind the Edelbrock manufacturing plant. Bob Pierson looks over the coupe's engine bay while NHRA's own Wally Parks looks over Bob's shoulder at El Mirage in 1950. At El Mirage in '56, the red and white coupe then owned by Tom Cobbs was one of the first to install a blown small-block Chevy into a race car. The coupe ran 198.86 mph under Cobbs' direction. The original seat, lost over the years, was straight from military surplus and was once ridding in a B-25 bomber. Note the weld in the back of the seat--it was narrowed 4 inches; and the original 6-volt battery--the car now has a 12-volt. Bobby Meeks, who worked at Edelbrock for 40 years, built the 267ci Mercury flathead engine fitted with Edelbrock 8.75:1 heads and intake, three Stromberg's, a Winfield Super H cam, Kong dual-point/dual-coil ignition, and Belond W-2 headers. Okay, the coupe is obvious, but can you identify the '36 Ford three-window? Yep, it's Bob Pierson's 121-mph Ford in 1950 at Bonneville. You could spend an hour looking over the vacated engine compartment with interest, such as the '39 steering box converted to crossover steering in the coupe. But, you really should enjoy the significance of the old time tow bar. Don't need no stinking trailer, just give 'em a tow bar! The end! Or, should we say, just the beginning. At speed! In red and yellow trim the car was then owned by Dawson Hadley and pushed the envelope to 165.23 mph. |